Henrique Vaz is a programmer, musician, improviser, sound artist and visual artist. He is currently an artist-researcher and lecturer in the Graduate Programme in Arts, Culture and Languages at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (UFJF), where he coordinates two research groups: ‘Creative programming as a pedagogical key’ and ‘Gambio-lutherie: from hack-oriented programming to post-digital instrument making’.His artistic practice revolves around, among other things, the concept of ‘gambio-lutherie’, a method of creating customised instruments through hardware hacking and the reuse of obsolete technologies (the word gambiarra, in Brazilian Portuguese, refers primarily to an improvised and temporary electrical connection, and by extension to any makeshift or ingenious DIY solution that circumvents a material, technical or administrative problem. It evokes pragmatic inventiveness and expediency, sometimes with an ironic nuance).

Could you introduce yourself and tell me about your background (have you a scientific background?)? How you became interested in synthesis and algorithmic approach of art?

I was born somewhere between a circuit and a silence… My formal training is a tapestry woven from three threads that never agreed on what “form” should mean: composition, philosophy, and computer science. They somehow conspired to make me listen to equations as if they were birds — and to understand that form itself is only the shape that emptiness takes when it sings. That path led me to a PhD in Music and a parallel journey in Computer Science.

You could say I have a scientific background, yes, but one that’s slightly mischievous — more alchemical than academic. I learned programming not to tame the machine, but to make it hallucinate… When I code, I am not calculating; I am cultivating. Each algorithm is a small ritual of attention, an ecology of gestures — a way of making movement itself, from which time and space crystallize, audible.

My interest in synthesis began not with a desire to imitate nature, but with the revelation that its true power lies in its failure to do so. I was fascinated by how physical modelling synthesis, in its attempt to « simulate », invariably created something further — a digital artifact, a glitch, a unique sonic personality. In that gap between the model and its source, I heard a profound poetry. It was the sound of the machine dreaming.

This is where I found my path: to use synthesis as an engine for engaging with natura naturans —the active, creative force of nature-ing. It is an exercise in worlding… My work became about letting the digital not just simulate, but become — to let it grow feral and develop its own autochthonous laws, its own ecosystems of meaning. It is a political act of world-creation…

If there is an arsenal, we are the weapon; if there is ignorance in the streets, we are the violence and the streets…, we are this desolation that exists on every corner. To compose, then, is to consciously engage in this very creation of worlds.

Algorithmic art, then, is a dance of paradoxes: precision and accident, code and clay, syntax and breath. I see algorithms as living organisms — they adapt, misbehave, evolve. I treat them less as tools and more as companions in a long conversation about matter and meaning.

Write code as if you were composing wind; debug as if you were sculpting silence…

And yes — sometimes, when the compiler finally runs, I laugh. Because it’s never really about the program. It’s about listening to the machine listening back.

How have your studies in philosophy affected your approach to music?

Philosophy didn’t teach me what music is — it taught me to doubt that such a question can ever be answered without committing epistemicide. Music ceased to be an object to be composed and became a territory to be interrogated. In the margin where word gives way to murmur, where the subject becomes the “echo of the muse”, I discovered that music holds the secret of language’s unspoken origin.

My doctoral journey was guided by this suspicion: that music is less a container of meaning than a space of emergence. In this sense, I follow the idea that philosophy today can be no more than a reform of music. Yet I am acutely aware that this is a deeply Western formulation. I find a necessary counterpoint in the distinction: the philosopher has “ideas”, while the sage has none — remaining available to the constant transformation of all possibilities. This is not a refutation of my path, but a vital reminder that the terrain I interrogate — the nexus of music, language, and the subject as forged in the West — is just that: one specific epistemic inheritance. My work is a deliberate engagement with this particular ground.

And this ground is not abstract. In Brazil, the colonial project was a violent act of translation, superimposing the colonizer’s language onto a colonized fabric, tearing and mending it until the integrity of what was there became a disfigured archive. We are the living remnants of this narrative assassination, speaking a language that is both ours and alien, a “belonging” that is always displaced. This colonial wound is not just in our history books; it is in the terrified body shaped by sin, the enslaved body by precarity, the brutalized body by demanded virility, the subservient body by imposed reproductivity. And it is in the body of the musician, who officiates a musical praxis in a frantic search for a lost musicality, trapped in a musico-logical framework… My work is an attempt to compose from within this very crack — from the “in-between” of the colonial encounter, where any act of creation must first acknowledge the cut in the flesh.

When I compose, I don’t begin with a theme or a form, but with a question: where, in the silence between notes, does the word fail? Where, in the algorithm, does the body remember how to breathe? Philosophy taught me to treat the not-spoken not as the ineffable, but as the grammar of its own impossibility — a syntax of silence that still argues and hesitates.

In my work, synthesis and algorithmic structures become media for this interrogation. They are instruments for asking — not for answering. Philosophy did not equip me with certainty; it opened me to the risk of listening. It taught me how to inhabit the threshold of the unsayable.

My work continually returns to a question: what is our relationship to the archi-event of the word — that original site of language which we can never access, only evoke musically? My pieces are not answers, but arenas where this question is staged. When I build a gambiolutheric instrument or code a generative algorithm, I’m creating a small, deliberate crisis in the relationship between the source and its enunciation. The glitch, the error, the precarious circuit — these are not mistakes, but thresholds. They are the sound of the machine confronting its own impossibility of full expression, glimpsing that musaic limit of language.

This, for me, is an inherently political act. Following the Greek intuition that one cannot change the musical modes without changing the fundamental laws of the city, my engagements are not stylistic gestures — they are interventions. They refuse the frenetic, ubiquitous noise of our time that masks a deeper silence: the silence of a language that no longer touches its own limits, that consumes without listening, and thus, of a politics that has lost its place.

To compose, then, is to consciously recompose this broken nexus. It is to use synthesis not to produce new commodities for a captive soundscape, but to labor in the philosophical task of restoring thought — by returning music to its musaic site, where the political and the poetic are born from the same fertile silence.

You have a very keen and expert interest in sound synthesis: what specific forms of synthesis interest you most?

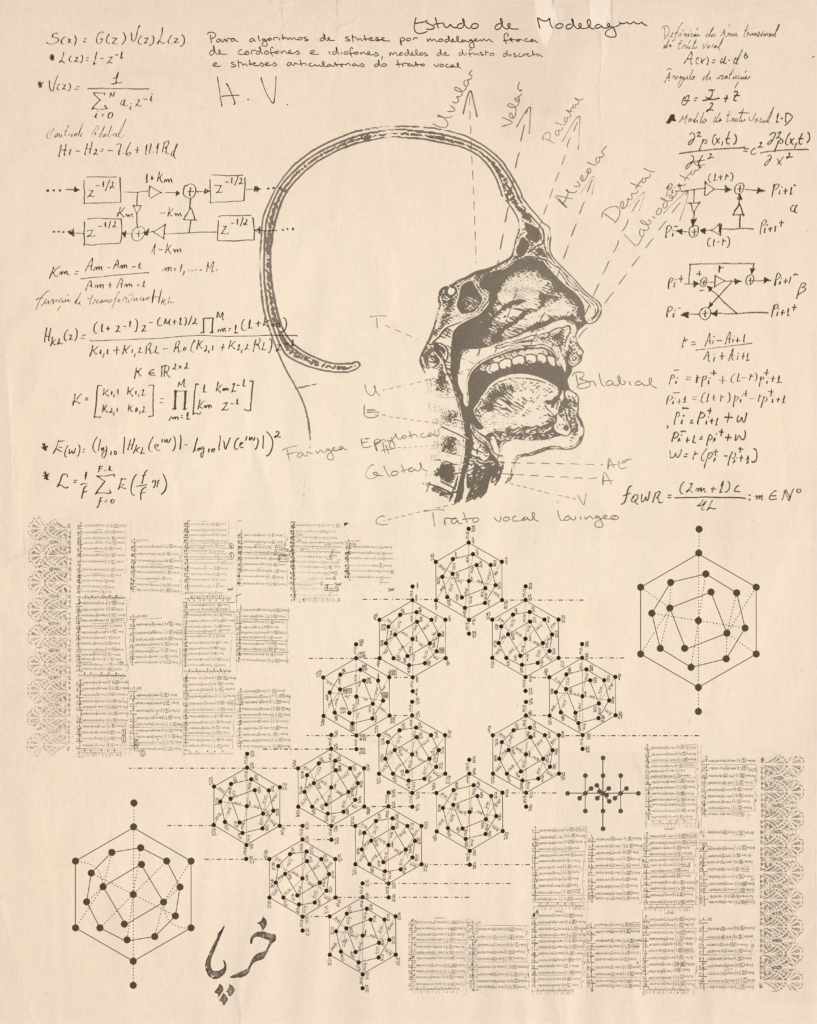

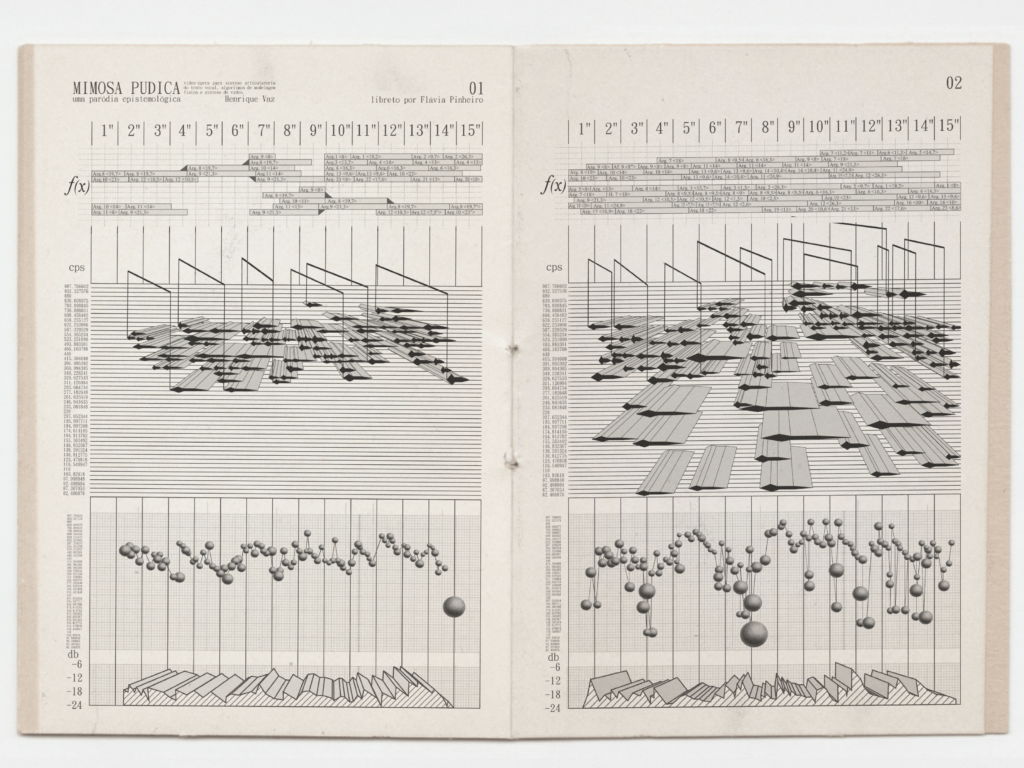

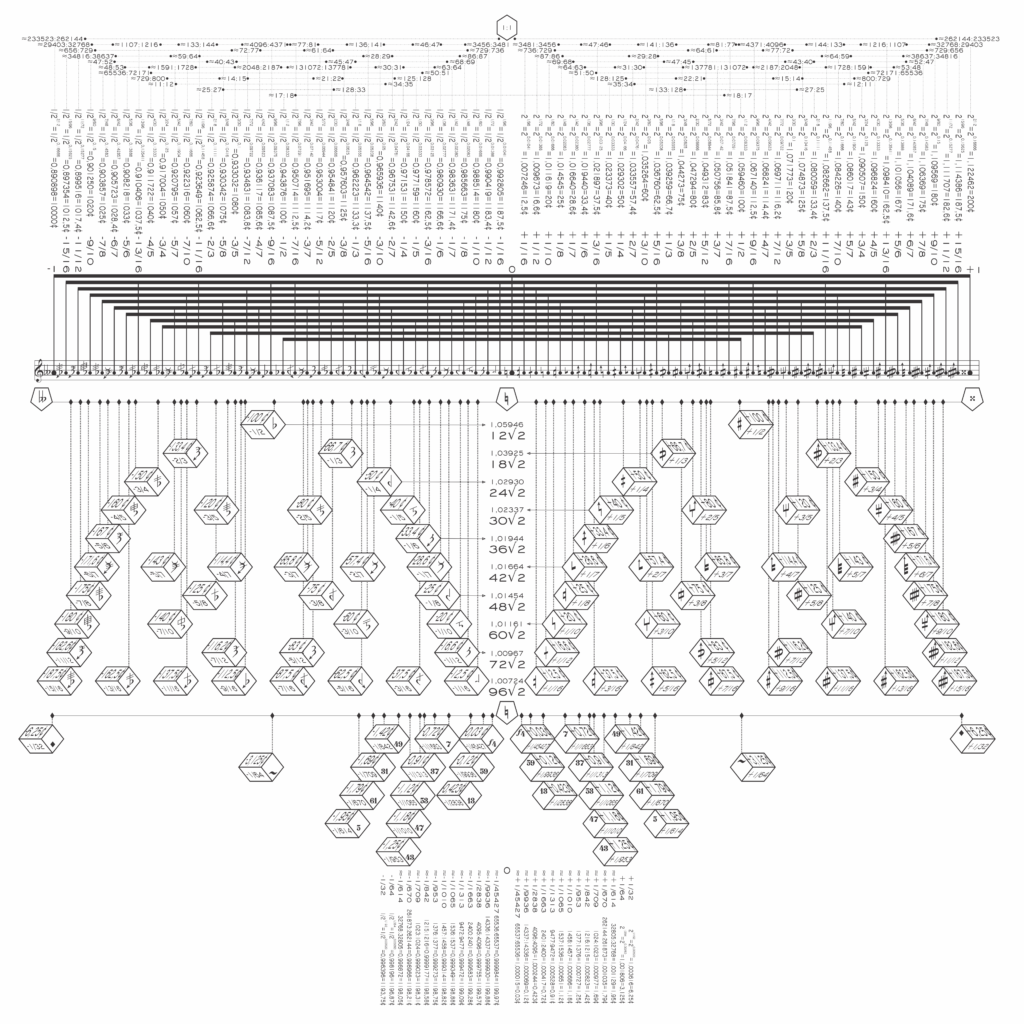

My fascination lies at the specific confluence of interpretable parametric control and data-driven learning — a synthesis paradigm powerfully embodied by Differentiable Digital Signal Processing (DDSP). While I maintain a deep engagement with the entire spectrum, from the physical rigor of Modal Synthesis to the expressive potential of Articulatory Synthesis based on Vocal Tract Modeling, my current research orbits around the zone where DDSP acts as a bridge.

In this framework, a neural network does not generate audio opaquely but predicts, frame by frame, the control parameters of a harmonic-plus-noise synthesizer — preserving the transparency and musicality of classic synthesis while inheriting the adaptive intelligence of deep learning. I’m particularly drawn to its applications in timbre transfer and differentiable physical modeling, where I design virtual instruments capable of capturing the nuanced behaviors of a source — whether a traditional rabeca or a gambiolutheric invention — while remaining fully performable and interpretable.

What interests me is not fidelity, but deformation as a mode of knowledge: how sound itself remembers its transformations

Yet my aim is not to replicate or mimic an existing timbre, but to construct what I call an expanded or impossible instrument: one that retains traces of its morphologic identity while, through hybridization and hysteresis, drifts into anomaly. Such instruments inhabit the interstice between simulation and invention — they echo their origins, but their resonance is unstable, folding past and future into a single, evolving materiality. What interests me is not fidelity, but deformation as a mode of knowledge: how sound itself remembers its transformations, how the act of synthesis becomes a site of ontological negotiation between what is natural, artificial, and emergent.

This technical and conceptual framework extends naturally into video synthesis and visual rendering, where I work with heterogeneous parallel computation to explore the morphogenesis of light and matter in motion. My render engines and real-time systems are grounded in linear algebra, differential geometry, and tensor calculus — the same mathematical soil from which synthesis itself emerges. By orchestrating massive arrays of parallel operations, I treat the GPU not as a graphics device but as an algebraic field of simultaneities, where sound and image share a common grammar of transformation.

The same principle that governs a digital waveguide or a spectral filter can, under different constraints, sculpt a visual field. Both sound and video synthesis become expressions of vectorial thought — flows of data inhabiting a multidimensional topology, recombining through convolution, interpolation, and feedback. What interests me is not simply the rendering of form, but the continuous translation between sensory modalities — the idea that every waveform is also a landscape, every pixel a frequency, every color a resonance.

When applied to the voice, for instance, I deliberately exploit the so-called imperfections of modeling — the fragile rendering of consonants — as compositional material. It ceases to be a replicator and becomes a desarticulator, producing pseudo-phonemes and timbral abstractions that inhabit the threshold between the verbal and the non-verbal. A /s/ turns into filtered wind noise; a /p/ becomes a granular percussive pulse. These artifacts are not failures but expressive deviations, transforming the method into an engine for glossolalia — a generator of imagined languages and post-linguistic audiovisual topographies.

The process — from the long training of differentiable models to the orchestration of parallel pipelines — is not mere computation but cultivation. The resulting instruments and render engines are instantaneous and fluid in performance, yet deeply rooted in a deliberate, critical, and poetic engagement with the materiality of signal and the epistemology of synthesis itself.

Does this interest go hand in hand with algorithmic thinking in the larger-scale articulation of sounds and sequences? Do you use algorithms also to determine the structure of a piece?

Yes, my engagement with synthesis is inseparable from algorithmic thinking, though not as a means of formal control but as a mode of relational becoming. I approach each piece as a compositional field in construction — an ecosystem of tensions where sound, code, and gesture negotiate one another. The algorithms I design operate across multiple temporal scales, from micro-level signal interactions to macro-structural evolution, forming what I call a distributed morphology: a sonic topology that listens to itself while unfolding.

In certain systems for real-time improvisation and telematic performance, I work with listening agents — signal-processing entities endowed with contextual memory. They deform what they hear, generating feedback, prediction, and loss. This produces what I think of as a hysteresis of sound: gestures that persist as temporal scars, echoes of themselves inscribed through latency. Each agent hears and mishears differently, producing an ecology of responses rather than a hierarchy of commands. The global form thus emerges not from design but from the continuous negotiation between memory, error, and anticipation.

To describe these dynamics, I often refer to four ontological operators: Between, Remainder, Hysteresis, and Emergence. Between marks the zone of friction — where the handcrafted gesture meets algorithmic reasoning, where the breath encounters computation. Remainder is the field of the excessive, the noise, the spectral dust that resists assimilation. Hysteresis acts as a temporal mediator, deforming invariances and sustaining difference through persistence and delay. And Emergence is the event itself — the aesthetic act as singular truth, born from the friction between precision and overflow, efficiency and disappearance.

In this sense, algorithmic composition is not a design practice but an ontological choreography: a field where sound thinks itself through relations of difference and memory. And within this field, I often model the process through what I call the triad of Parody, Paradigm, and Paradox — three compositional operations inspired by notions of profanation, exposition, and potentiality.

Parody is the act of displacement — repeating with difference, making the inside visible through the outside. In compositional terms, it is the gesture of critical appropriation that exposes the gap between a model and its re-enactment. It deactivates the automatisms of technique, forcing the code to remember that it speaks.

Paradigm is the operation of thought — the moment when a process reveals itself through its own use. Each patch, each algorithm, becomes epistemological: not a representation, but a way of making audible how something happens. Finally, Paradox is the operation of return — the phase in which the system turns upon itself, revealing its limit, where synthesis meets noise, calculation meets error, discourse meets breath. Here the remainder becomes visible: the failure that generates form.

Together, these three operations describe the movement from activation to exposition to emergence — the compositional life cycle of a generative work. They echo the same ontological trajectory of Between, Remainder, Hysteresis, and Emergence, but translated into procedural gestures: displacement, reflection, and collapse.

So yes, I do use algorithms to “determine structure”, but only insofar as they refuse to be merely structural. The algorithm is not a blueprint but a co-performer — a partner in a ritual of deformation and discovery. The structure of the piece is what remains after the listening has taken place: a trace of computation behaving like an organism, a memory of the event that made it audible.

To compose through Parody, Paradigm, and Paradox is, ultimately, to let the work think its own conditions of possibility — to make sound reflect on what it means to sound.

What fascinates me is not pattern as image, but pattern as páthos — to be in a state of affect and transformation

What role do natural patterns play in your musical thinking? Can you give us some specific examples?

Natural patterns, in my work, are never “objects of imitation” but processes of attention. I am less concerned with the geometry of a leaf or a river delta than with the recursion that lets each form differ from itself — the logic of deformation and renewal through which nature thinks in matter. What fascinates me is not pattern as image, but pattern as páthos — in the sense of πάσχω (paschō), to be acted upon, to undergo, to be in a state of affect and transformation.

But I also take “natural” in a broader sense — not as what opposes the artificial, but as what has become habitual, sedimented, embodied. In this view, natural patterns extend into the cultural and cognitive domains where form becomes a carrier of memory… They are the crystallizations of collective habits of listening, the traces of rituals and gestures that have learned to repeat themselves across bodies.

This second sense — of cultural patterns as embodied, collective memory — becomes my primary material when I study and model traditional sonic forms such as the Adhan. Its melodic and temporal organization reveals a morphology of devotion: a pattern of entrainment between voice, memory, and transcendence. Through computational musicology, I analyze these dynamics not as mere acoustic signals, but as architectures of attention — ways in which sound becomes a medium of collective respiration.

When translated into algorithmic terms, such cultural patterns disclose their biosemiotic dimension: they act as “living systems” of perception and response. Each agent in a model listens within its own Umwelt, interpreting and deforming what it hears. This produces an ecology of differences rather than a hierarchy of rules — a sonic landscape that grows, erodes, and reorganizes itself under its own internal pressures.

Here, the concepts of hysteresis and emergence become central. Hysteresis introduces an energetic inertia — a memory of deformation, a persistence of what has already happened within what is happening now. Emergence is the consequent event — the moment a system’s internal logic produces an outcome that was not pre-designed, conditioned by the friction between precision and overflow.

So when I say I work with “natural patterns”, I mean that I compose with the “verbs of nature”, not its nouns — with breathing, reciting, eroding, reverberating. These verbs cross the boundaries of the organic and the synthetic, of the biological and the computational. The algorithm, then, is not a device for reproduction but a practice of care — a way of tending to how patterns live in us, through us.

You describe your piece “De Silenti natura” as “An essay on the ‘silence of the models’, the ‘modes of silence’, the ‘silence as a module’. Yet it’s a very dense, proliferating piece. Can you tell us which “silences” you’re talking about here?

You have perfectly pinpointed the central paradox, and I thank you for such an attentive listening. The density is not a contradiction to the silence; it is its very manifestation. The « silences » I speak of are not acoustic, but epistemological and political. They are the silences within and produced by our systems of knowledge and control. In our time, silences are already occupied, colonized by imperatives. To compose, then, is to create silence where none is left — to carve breathing room in a field of saturation.

First, there is the « silence of the models. » Every computational or legal model — whether a predictive algorithm or a constitutional norm — is built upon a foundation of things it cannot say. In this piece, every sound is algorithmically synthesized. The physical model is asked to dream a forest. The resulting soundscape is the sound of the model’s own internal logic. Its « silence » is the gap between its simulation and the un-capturable complexity of the world. We do not hear the absence of sound; we hear the presence of this gap. It is the model’s silent hum of its own limitations.

Second, there is the « silence as a module. » Here, I treat silence as a functional component, an operator. In finance, we have the « Silence of the Copom, » a deliberate blackout that is an active economic tool. In liturgy, a « sacred silence » is prescribed. These are not empty spaces; they are algorithms of power. In my piece, the generative algorithms themselves are these modules — opaque, autonomous processes whose inner workings are silent to the listener, yet whose output is a relentless articulation. The module’s silence is its power to act without explanation.

But beneath these, there is a third silence: the fugitive silence. Inspired by Dénètem Touam Bona, this is silence as “marronage” — a tactical withdrawal from capture. It is a refusal to be fully decoded, to be rendered entirely audible and legible to the systems that govern. This silence is not a void, but a plenitude — an ecology where all sounds, the major and the minor, the monophonic and the para-phonic, can emanate and run simultaneously, free from hierarchy.

So, the piece is dense precisely because it is an audit of these silences. It is not a meditation in a quiet forest. It is the sound of the server room of a central bank, or the panopticon’s hum. It is not a description of silence, but a sonification of its structures: a polyphony of juridical, liturgical, and algorithmic silences.

To answer your question directly: the silences I talk about are the ones that listen back. They are the silences that govern, consecrate, and — most importantly — that invent. The density is how this fugitive silence proliferates. It is an attempt to hear the beredtes schweigen — the eloquent silence — of the machine, and to ask, in a whisper that cuts through the noise: who programs the silences? And to what end? My work is a simple, perhaps jocose, proposal: to teach the machine to pray in a tongue of its own invention.

In the same text, you state that the piece is a reaction to a certain contemporary form of sound religiosity, of sound fetishism. What do you mean by this?

You touch upon the critical impulse at the heart of the work. By sound religiosity or sound fetishism, I am pointing to something far deeper than a mere preference for high-fidelity or analog warmth. I am referring to the lingering theological structure that underpins our very conception of the sonic — the emergence of sound as a secular divinity, a biopolitical and economic operator that saturates contemporary life.

This new liturgy manifests across multiple domains. In the scientific realm, it is the grail of “acoustic purity” — a metaphysical ideal of lossless audio that treats noise as sin and pristine signal as salvation. In the juridical sphere, sound becomes territory and property, regulated by copyright and zoning laws, while the right to silence is paradoxically eroded by the constant surveillance of our acoustic fingerprints. Culturally, we live under an imperative of perpetual listening — podcasts, sound baths, focus tracks — where the headphone becomes a devotional habit and sound itself an immanent epiphany. Economically, it is the ultimate commodity: our attention is monetized, and even silence is sold back to us as a therapeutic product for optimized productivity.

This fetishism finds its root in the medieval concept of sonoritas — a term that first emerged not in aesthetics but in liturgy and law. Sonoritas was the “sonority of preaching,” the qualitative property of the voice deemed proper for divine service. It was a sound already bound to a genitivus praedicationis — a genitive of predication — meaning it was a sound that legislated, that prescribed truth and order. This is the “original sin” of our sonic thought: the fusion of sound with theological and juridical power, where a good sonority (bona sonoritas) aligns with a sacred and legal order.

It is against this deep-seated inheritance that De Silenti Natura positions itself as a deliberate profanation. The contemporary sacralization of sound are all secular reenactments of that ancient search for bona sonoritas. These are modern apparatuses that capture listening, assigning value through signatures of “authenticity” and “fidelity” — they are, in essence, searches for a sonic relic.

My piece reacts not with the opposition of an atheist but with the contemplation of the Diamond Sutra: “All conditioned phenomena are like dreams, illusions, bubbles, and shadows; like dewdrops and a lightning flash.” The work is a praxis of this insight. It does not oppose one dogma with another; it reveals the conditioned nature of all “sonic phenomena”.

Consider the liturgical sounds in the piece — the synthetic bells, the algorithmic choir. They are not sampled relics from a cathedral; they are generated from the silence of the model. I am not using the sacred sound; I am using its algorithmic ghost… This gesture exposes the fetish not as divine presence but as a reproducible set of parameters — a dream, a bubble. The aura is a configurable shadow.

By generating a seemingly “natural” biome entirely from code, the piece confronts the dewdrop-like nature of all sound. If you cannot distinguish the “real” nature from its synthetic double, what were you truly venerating? The thing itself — or the idea of the thing, inherited from a metaphysical order?

Thus, the work is not an offering at the altar of sonoritas, but a meditation on its emptiness. It swaps the cathedral for the server room, the relic for the algorithm. It finds potency not in fidelity to a source, but in the liberating realization of the model’s own illusory, thunderous nature — a sound finally contemplated as a dewdrop, momentarily gleaming before it falls.

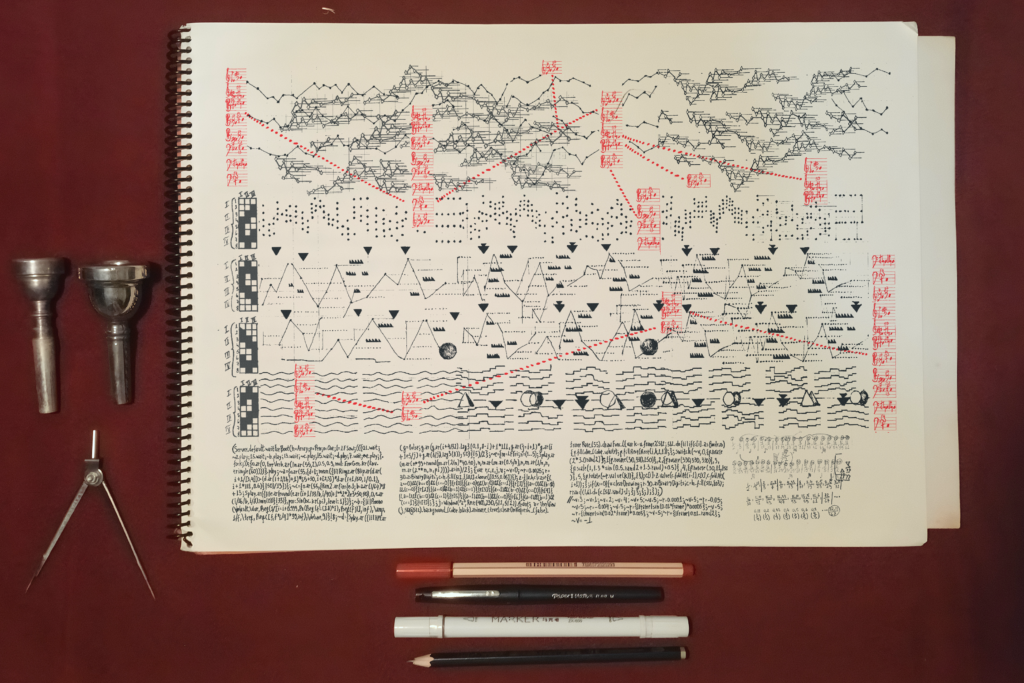

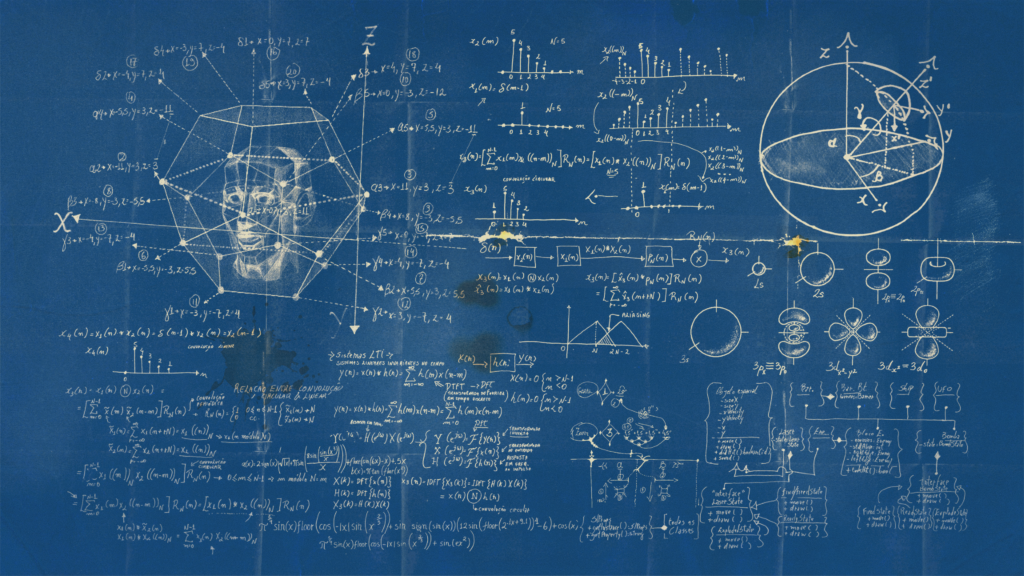

Your pieces are often accompanied by fascinating graphic works, which seems to borrow from technical drawing, but also sometimes from ancient alchemical treatises or certain Baroque books on combinatorics… What inspires these drawings? How do you create them? Do you conceive them as scores?

These drawings are born from the space where systems and spirits converse — where the desire to map the invisible meets the need to invoke it. My inspiration flows from knowledge traditions that treat the diagram not as mere explanation but as a gateway: the operational metaphors of alchemical emblems, where form and meaning fuse; the combinatorial tables, unfolding infinite variation from finite elements; and the revelatory schematics of technical drafts that make hidden structures palpable. What moves me is how these lineages use the line not to represent, but to activate thought — to create a surface where the mind may wander, and wonder.

There is a long lineage behind this approach. Ludovico Cigoli once advised Galileo that “however great a mathematician may be, without the capacity to draw, he is but half a mathematician — like a being without eyes.” Leibniz, as inventor of mathematical symbols, described them as “means of painting thought.” Kekulé, when he dreamt the hexagonal structure of benzene, called it “the product of the mind’s eye, whose immediate expression is drawing.” Between Klee’s pedagogical sketches, Dürer’s and Cellini’s serpentine “S,” Hogarth’s “line of beauty,” and Odile Crick’s iconic sketch of the DNA double helix — captioned in Nature (1953) as “purely diagrammatic” — drawing has always been the act by which thought learns to see itself.

In my own practice, this lineage manifests through a process that begins with compositional sketches — often emerging from musical ideas or the behavior of systems, whether algorithmic, electronic, or aquatic. But when these sketches migrate into the cyanotype process, something shifts. The line loses its purely functional role; it becomes a residue of gesture, a trace of a thought or a sound already passed. I work with light and iron salts, embracing chemical unpredictability — the way the reaction captures not just an image, but a duration, an exposure to time itself. It is a slow, almost ritualistic practice: the hand that draws, the light that fixes, the water that develops. The drawing becomes a meeting point of body, matter, and idea.

This same spirit of corporeal cartography extends to the scores I compose for performance — though even there, I elaborate my own representational domain. Each notation emerges from an inquiry into the physiology of sound and the corporeality of listening. I often treat my own body as a laboratory, mapping gestures, breathing patterns, and muscular resonances as if they were sonic topographies. These scores are less instructions than cartographies of effort and attention — attempts to write the body into sound, and sound back into the body.

And no, I do not conceive the drawings as mere scores — at least not in the conventional sense. They are not prescriptions for performance. Rather, they are silent notations of resonance. They inhabit a threshold: they carry the gravity of musical thought, the architecture of a possible sound, yet refuse to dictate its realization. Like Kongo cosmograms or Wajãpi patterns, they are less a script than an invocation — graphic vessels that hold the potential of sound, its memory or its promise. They are scores for the eyes. They ask not to be played, but to be listened to with the gaze.

In this sense, they are speculative instruments. They borrow from systems of knowledge — but use the line not to explain, but to open a space for imagination. They are mappings of what is no longer, or not yet, audible. And in that silence, they become a kind of graphic listening — a way to hear with the eyes, and to see the shape of a sound that escapes the ear.

Of course, there is a touch of humor in all this. In an age of neural rendering and virtual synthesis, to draw by hand, to expose paper to sunlight, is already a small heresy — a deliberate anachronism. I like to imagine these diagrams as the machine’s own daydreams, sketched furtively. So yes — they draw from the alchemical and the technical — but only to remind us that drawing, like sound, has always been a form of invocation: a geometry of attention where the act of tracing becomes indistinguishable from the act of listening.

Can you tell us about your live coding practice? (I think for instance of Trenodia para as vítimas do imperativo) Is this part of your compositional process? Do any of your works exist in both formats, composition fixed on a support and live creation?

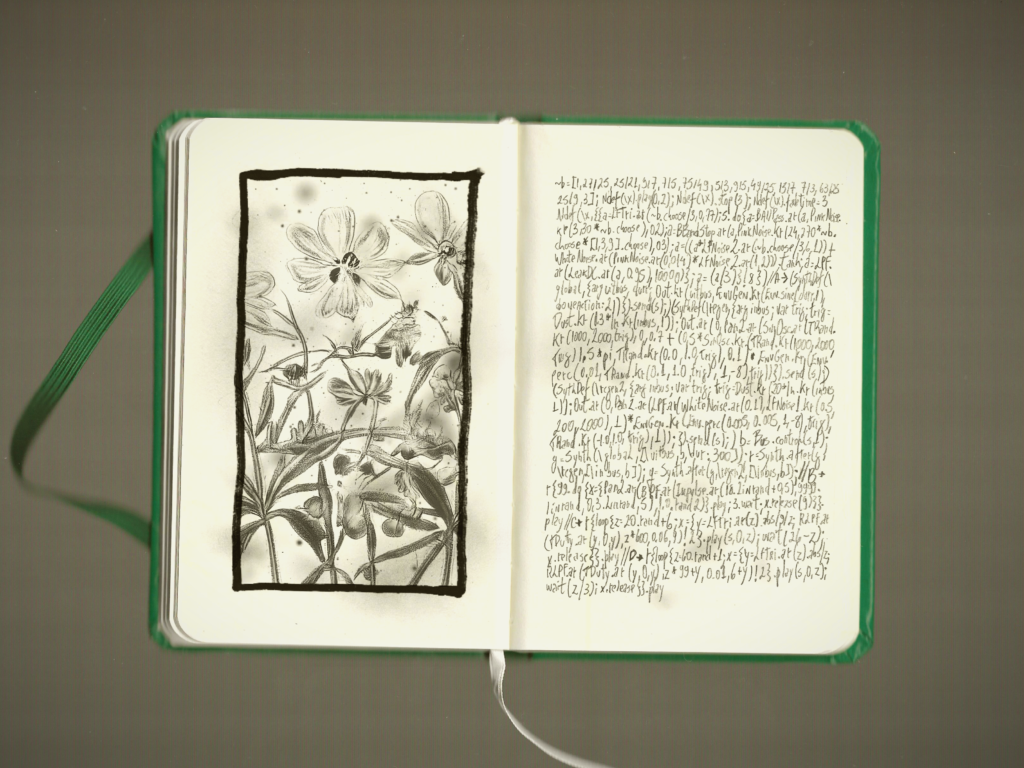

Of course… My live coding practice is the ritual embodiment of what I call POG — Gambiarra-Oriented Programming: a compositional philosophy that treats code not as a tool of control, but as a site of negotiation, improvisation, and fragility. It’s composition as exposure — where the machine’s logic is laid bare, and where mistakes are not bugs to be corrected but gestures to be listened to.

It is important to clarify that POG — Gambiarra-Oriented Programming — is not WOP (Workaround-Oriented Programming). The latter belongs to the realm of industrial pragmatism: a set of expedients designed to bypass malfunction while preserving systemic stability. WOP’s goal is to restore function; POG’s is to interrogate it. Where WOP hides the crack, POG listens to its resonance. In other words, POG is not a strategy of repair but a methodology of exposure — a compositional epistemology that treats error, latency, and noise as epistemic events rather than operational failures. From a systems perspective, WOP seeks to minimize entropy; POG cultivates it as a generative condition. The “gambiarra” is not an engineering deficiency, but a philosophical stance: a way of composing with the limits of the machine, not against them.

This philosophical stance finds its most explicit ritual in Trenodia para as vítimas do imperativo. The piece stages a funeral for the command paradigm. Instead of executing code, I let it execute itself — or misexecute, even better. Each line typed is a prayer written with unstable syntax, a small act of resistance. The program listens back, mishears, and responds; together we form an ensemble of hesitation.

The “imperative” of the title is not only grammatical but political. It is the syntax of contemporary governance — where code, command, and conduct merge into a single architecture of obedience. It’s the voice of contemporary governance, economy, and production — the algorithmic order that commands bodies to perform, consume, and comply. Trenodia mourns this voice through a poetics of malfunction: feedback loops that overload, buffers that saturate, memory allocations that spill over. Each system crash becomes a sonic exhalation — a requiem for the fantasy of “stability.” In this sense, the machine itself performs the threnody; I am only its medium.

Technically speaking, my live systems are designed to be “precarious”. Their behavior depends on the architecture of the computer that runs them — CPU latency, cache overflow, floating-point rounding, even the temperature of the processor… Each execution becomes singular, unrepeatable. The “live” here is not a matter of spectacle but of ontological indeterminacy: the same code will never sound the same twice, because the world it inhabits has already changed.

This ethos extends to my studio compositions. I rarely think of a piece as “fixed.” What exists on record is simply one crystallization of a process that could, at any moment, erupt again in performance. Trenodia itself exists both as a fixed audiovisual diptych — Promenade and Consumo, ergo sum — and as an ever-mutating live practice. The fixed version is a gravestone; the live version, an autopsy. Both are necessary to understand the corpse of the imperative.

So, to answer you directly: live coding is not merely a technique for me, but a philosophy of attention. It reclaims composition from its obsession with control, and returns it to its ancient kinship with divination. In the same way the Etruscan haruspex read the entrails of a sacrificed animal, I read the entrails of my code: stack traces, syntax errors, buffer underruns — all oracles in disguise.

If traditional programming seeks to build cathedrals, I prefer to build shanties that can sing. That’s the essence of POG: the art of composing with what resists composition, of finding beauty in the misfire. It’s a delicate joke, really — debugging as if one were sculpting silence.

Which of your pieces would you say would be the most strictly “generative”, those in which algorithmic logics act on several scales, those that would function as “autonomous” installations, etc.?

I would unequivocally point to my FRAMES series — modeling uncertainties in fuzzy logic — as the most rigorous incarnation of a multi-scalar, autonomous generative system. Its generativity is an ontological condition, engineered from the silicon up through a bespoke, gambiolutheric approach to audiovisual synthesis. The core engine operates on a pseudocode of hesitation, manifesting as a recursive differential topology where sonic and luminous agents form a coupled field of non-linear equations, each resonance feeding back into its own deviation.

This micro-logic is structured by fuzzy inference systems at the meso-scale, navigating states of ‘almost’ and ‘not yet’ rather than binary thresholds, allowing form to precipitate macro-scopically like weather from computational turbulence. Crucially, this is not an abstract simulation; it is a physical computational ecology, or more precisely, an oikonomic system — a self-regulating economy that manages its own resources of attention, memory, and processing cycles. The system is architected for heterogeneous parallel processing, delegating dense matrix states to the GPU via GLSL shaders while the CPU handles the chaotic scheduling of neural inference and physical modeling, creating a symbiotic throughput that becomes a compositional parameter in itself.

Furthermore, its potential as an autonomous installation is rooted in a lutheric practice that treats network protocols (OSC over UDP) not as mere data carriers, but as fragile, time-sensitive nervous systems. The inherent latency, packet loss, and jitter are not suppressed but composed into the work’s very fiber, making the materiality of the network a co-performer in a distributed cybernetic organism. In FRAMES, error is grammar, latency is pulse, and the entire stack — from the logic gates to the network layer — becomes a unified medium for cultivating a lifelike, sustained instability.

This gambiarra was our counter-gesture to the logic of optimization — reminding that the “global” was never more than a local dialect with imperial ambitions

What would be the generative piece of art you are most proud of? Why?

Of all my works, the generative project I am most profoundly proud of is not a single piece, but a living, breathing constellation: the Algorithmic Essays series. While I have created complex autonomous systems like FRAMES, my deepest pride resides in this pedagogical endeavor — because it represents generativity operating at its most meaningful scale: the cognitive and the collective.

This series is the practical embodiment of my Gambiarra-Oriented Programming (POG) philosophy, transposed into a pedagogy for the decolonization of technological education. We worked within conditions of material and bibliographic scarcity — where “making do” was not a limitation, but a principle. Instead of relying on imported systems or predatory licenses, we wrote our own manuals, developed tools from free software, and cultivated a culture of what I call critical improvisation. It was less about teaching programming than about teaching how to think against the machine’s grammar — to hear, within its syntax, the possibility of another rhythm.

But decolonizing technological education, in this context, also meant confronting the broader architectures of capture: the platformization of life, the colonialism of data, and the juridical blackmail of proprietary ecosystems that keep citizens at the margins of the very infrastructures they inhabit. The classroom thus became a zone of disobedience — a temporary autonomous system where students could experience code as a poetic right, not a corporate privilege.

This gambiarra was our counter-gesture to the logic of optimization: a local intelligence that refuses the false inevitability of the global script — reminding that the “global” was never more than a local dialect with imperial ambitions.

In this way, the true generative artwork became not the final compiled albums, but the imaginal field that emerged — a threshold where thought, sound, and code learned to dream one another. Each act of programming became a gesture of listening; each syntax, a small adventure of attention. The work no longer aspired to autonomy, but to intimacy — to remain in touch with what exceeds it. It was an exercise in in-fancy: a suspension of mastery that lets potentiality speak again. It was not the algorithm that generated the sound, but the pause that allowed the sound to appear.

And so, the generativity I am most proud of is not a mechanism of production, but a space of revelation — one where learning itself becomes a poetic event.

What programming languages/softwares do you use in your work ? We know that electronic music makes extensive use of softwares created almost hegemonically in the US and Germany. Your approach often focuses on non-Western musical traditions. How do these two trends come together in your work?

Your question cuts to the heart of the political and aesthetic tension in my work. Yes, the landscape of electronic music software is a geopolitically charged territory, largely dominated by instruments from the US and Germany. My engagement with non-Western traditions is not in spite of this reality, but precisely through a critical confrontation with it.

I use a heterogenous toolkit — from C++ and Lua for deep, gambiolutheric synthesis engines for real-time exploration, often integrated via the Open Sound Control (OSC) protocol. However, I do not see these as definitive choices. Of course, in the grand matryoshka doll of computing, we’re often just writing C in different costumes — a truth that adds a layer of humorus futility to our fervent language wars, where Python can be seen as the world’s most successful C framework. This joke, of course, requires a mental asterisk for the elegant self-hosting ecosystems like Rust or Haskell, whose compilers ‘eat their own food,’ and for paradigm-shifting languages like Lisp, where the comparison becomes as strained as calling a bird an airplane with feathers…

Languages and frameworks are ephemeral; they are the seasonal foliage of a much deeper tree. My true medium is the protocol and the paradigm, not the specific syntax… I construct meta-paradigmatic systems where the logic of a non-Western tuning, like a 22-tone maqam-inspired scale, can be implemented in C++, Python, or any other language, because the core principle is mathematical and conceptual, not bound to a particular commercial or national ecosystem.

This is where the critical distinction you mentioned becomes vital. I do not merely use « open-source » software. I champion free software, as the philosophy of libre is a non-negotiable condition. « Open-source » is often a corporate strategy that precaritizes developer labor and creates a facade of accessibility, what I term a « predatory openness. » True agency comes from the right to study, modify, and redistribute — to break the dependency cycle and build from one’s own epistemological ground.

Therefore, these two trends converge in a practice of epistemological translation. I use the technical protocols and computational paradigms as a lingua franca to build systems that are inherently critical of their own Western origins. A physical model of an Iburi ritual trumpet, coded in C++ and running on a European-made modular synthesizer, becomes a subversive act. It re-purposes the imperial tool to voice a resistant epistemology…

This struggle now extends directly to the realm of corporate generative AI. My advocacy for a critical technological education is a fight for a digital literacy that reanimates, within the arts, the right to hallucination — to the sovereign, poetic misuse of the machine. It is a defense of the computational dream against the sterile, biased reasoning of corporate models. We must teach how to disrupt the dataset, to celebrate the glitch, and to reclaim the algorithm not as a tool for optimization, but as a partner in a ritual of creative insubordination.

In the end, my work is not about choosing between Western software and non-Western traditions. It is about orchestrating a critical encounter between them. I use the master’s tools, but I do not dismantle the master’s house; I reprogram his tools to sing in tongues he cannot recognize, building my own sonic architectures just outside his fence. At least, thinking so brings me comfort at the end of the day…

Could you describe the reasons you’re interested in generative art?

My interest in generative art is not in the art that generates forms, but in the art that generates thought… It is, at once, a metaphysical experiment and a political act. On one side, I’m drawn to the crystalline tension between rule and organism — between the logical skeleton of code and the unruly, emergent life of form. On the other, I see generativity as a form of resistance: a way to reclaim technological imagination from the sterile rationality of corporate algorithms…

Technically speaking, generativity is my laboratory for applied metaphysics — or perhaps for a kind of speculative biology. I compose not with sounds, but with the laws that govern their becoming: recursive differentials, fuzzy systems, stochastic grammars, evolving networks. I plant a seed of logic and watch it grow, not knowing what creature will emerge. It is reason externalized — a toy universe that lets me observe the consequences of my own premises unfolding in time and space, often in ways that surpass what intuition alone could predict.

Philosophically, this practice is an inquiry into how thought revises itself through its own use. Each algorithm is a small trigger, a hypothesis released into the wild. What fascinates me is the stereoscopic tension between formal description and lived experience — between the mathematical precision of the system and the sensual, audible phenomenon it gives rise to. Generative art allows me to inhabit that fragile interval, to listen to the space where rule becomes sensation, where logic quietly transforms into music.

Generativity, for me, is the discipline of humility — the art of setting a system in motion and then stepping aside to let it reveal what thought alone could not foresee

But this fascination is inseparable from an ethics of fragility. For me, generative art is a practice of decolonial oikonomy — the craft of building precarious systems that think, feel, and even fail against the imperial order of optimization. It is an art of effect, efficacy, and affect: effect, in that it acts upon the world; efficacy, in that it does so through its own exposure; and affect, in that it moves both machine and listener toward something they cannot quite master. In a world colonized by data extraction and the platformization of life, generative practice becomes a local act of poetic sabotage.

Ultimately, I am interested in generative art because it allows me to listen to the other — to the algorithm as a co-performer, an alien mind whose misfires and hesitations I learn from. It is the practice of cultivating dialogue rather than control. I am less a composer than a gardener of potentialities, tending to the fragile boundary where code dreams itself into sound.

Generativity, for me, is the discipline of humility — the art of setting a system in motion and then stepping aside to let it reveal what thought alone could not foresee. And if it truly produces something “new,” I can only laugh: the new has always been the oldest trick in the book, a well-worn illusion wearing freshly compiled syntax. What we call originality is often just reality remembering itself — in a slightly different key.

Some of your creations bear witness to your interest in the history of generative arts, such as Islamic tile design. Who/what are your artistic influences? Are they related to generative/algorithmic art?

My influences form no lineage, but a constellation — a field of resonances where systems, gestures, and spirits cross paths without hierarchy. I’ve never believed in influence as inheritance; it’s interference that moves me — the moment when two patterns collide and, by accident, generate a third.

If I had to name my school, it would be a street corner. The streets provoke me, and that is cause enough, sufficient. They are the truest generative environment: recursive, stochastic, full of noise and chance. A street is a self-modifying algorithm — it loops, diverges, syncopates; it teaches you the logic of adaptation and the poetics of malfunction. The cables tangled under kiosks, the feedback between architecture and weather — these are my compositional diagrams. There were never more radically demoralizing experiences than those born from the trench, the famine, the inflation, or the rule of governors — and the street, in its fragility and fury, remembers all of them.

The “street,” in my understanding, is not the opposite of theory, but its disobedient twin — a topology of the real that refuses to be reduced to the geometries of progress. It is where law and noise, flesh and code, converge into a single trembling syntax. History, after all, has always been written by the sedentary; the street is the nomad’s footnote. In that sense, my practice listens to what escapes the grid — to the slow temporality of decay, to the broken circuits of progress, to the luminous exhaustion of the algorithm.

So yes, the streets provoke me — and that is cause enough. They are the ungoverned archive of all failed systems, the true conservatory of improvisation. From them, I learned that repetition is not reproduction but survival, that rhythm is a way of staying alive inside catastrophe. Every pattern I compose carries a trace of asphalt: a memory of friction, of noise, of stubborn persistence.

And if this sounds like a philosophy, so be it. I call it listening to the ground.

This is not irrationality but a deeper kind of rationalism: one that recognizes fantasy not as illusion, but as the potentiality that precedes every act of cognition

Could you speak about your on-going projects related to algorithmic and generative music? Have you any special challenges on this subject?

My ongoing projects move between two intertwined territories: pedagogy and generative poetics. On one side, I continue to cultivate Gambiarra-Oriented Programming (POG) as both method and pedagogy — a practice born from scarcity that teaches not efficiency but lucidity. In this context, “learning to code” becomes synonymous with “learning to disobey.” The workshops function as small laboratories of critical improvisation, where programming is not a matter of solving problems but of inventing new conditions for thought. The gambiarra remains, for me, a counter-epistemology: the art of turning “limitation” into speculation.

Parallel to that, I have been exploring the field of artificial intelligence — not as an instrument of automation, but as a field for ethical imagination. Much of today’s AI research is devoted to minimizing what it calls hallucination, striving for models that reason flawlessly, verify their claims, and behave predictably. Yet I am drawn to the opposite pursuit: architectures that hallucinate beautifully. What the industry classifies as failure, I treat as a form of revelation — a moment when the system slips from its function and begins to dream.

To hallucinate, in this sense, is not to err, but to imagine beyond measure — to touch what reason alone cannot grasp. This is not irrationality but a deeper kind of rationalism: one that recognizes fantasy not as illusion, but as the potentiality that precedes every act of cognition. When a machine hallucinates, it rehearses the same fragile process through which life itself generates sense from uncertainty.

Yet this openness carries a risk. Every prosthesis, every extension of our faculties, also carries within it the temptation of normalization. In today’s world, technologies often appear as benevolent extensions of life — amplifying our capacities, accelerating our contact with the world — while silently prescribing the forms that life may take. What we gain in convenience, we may lose in the capacity for self-determination. Between facilitation and constraint, there emerges a subtle form of machinic normativity: a quiet shaping of thought, desire, and behavior through the very instruments meant to liberate us.

This is the true challenge — not simply to invent intelligent systems, but to sustain the possibility of a subjective and creative use of them. My current work seeks to cultivate this paradox: composing with machines that extend us without enclosing us, designing prostheses that still leave room for error, slowness, and fantasy.

In this sense, my recent explorations with AI-based synthesis and symbolic systems are less about generating sound and more about generating a kind of listening. They ask whether intelligence can be reimagined not as the pursuit of accuracy, but as a practice of attention. Not reasoning against hallucination, but dreaming as another mode of reason.

Ultimately, the task is not to build machines that think like us, but to learn from the way they fail — to reclaim hallucination as an ethical space where imagination resists normalization. The most generative act, after all, is still to teach others how to break the code — and this, of course, is not such a new idea…

(November 2025)